Zakaria Zubeidi: The Palestinian Revolutionary and Artistic Leader Who Escaped ‘Israeli’ Prison

By Zoe Lafferty | MEE

It's been a year since Palestinian political prisoner Zakaria Zubeidi and five others dug a tunnel out of a high security ‘Israeli’ prison using a spoon – an act that galvanized Palestinians across the world.

I first met Zakaria in 2010 when I began working at The Freedom Theatre in Jenin Refugee Camp.

"Meet ‘Israel's’ most wanted man," the late Juliano Mer-Khamis, the theatre's co-founder and artistic director, jokingly said before adding: "My right-hand man, who without, nothing in this theatre would be possible."

Zakaria was one of the leaders of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades and is often described as an unusual theatre co-founder.

But across the years, I learned that it was his commitment to his community, unshakeable belief in Palestinian rights and creative resistance tactics that make him a truly unique artistic leader.

Zakaria got involved in theatre through his mother, Samira Zubeidi, who, during the First Intifada [1987-1993], joined activist Arna Mer-Khamis to create a network of children’s homes, providing alternative education.

After winning the Right Livelihood Award, they opened The Stone Theatre, Samira offering to build it on the top floor of her house. It was there, as a child, that Zakaria met actor, director and son of Arna, Juliano Mer-Khamis.

A life defined by occupation

The younger Zubeidi grew up under occupation, was shot by ‘Israeli’ soldiers during a protest, imprisoned and lost his father, a teacher, from cancer while young.

In 2002, during the Second Intifada, Zakaria's mother Samira and brother Taha were killed by ‘Israeli’ snipers, and their family home, along with The Stone Theatre and much of the camp was bulldozed.

Zakaria turned to armed resistance and would tell us terrifying stories of surviving the ‘Israeli’ invasion of the refugee camp in Jenin and of the community that kept him alive, leaving food in secret places and allowing him to hide in their homes.

His survival led to him rising up the ranks in the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. And in 2007, after the Second Intifada had ended, Zubeidi was included in an amnesty offered by the ‘Israelis.’

Juliano Mer-Khamis returned to the camp, and together with Zubeidi founded The Freedom Theatre, building a unique brand of cultural resistance.

It was a radical political and creative movement of artists who raised their voices against all forms of discrimination and helped bring the Palestinian cause to the attention of the world. "Somebody needs to tell the story of the fighter…You cannot just take a picture and write he is a ‘terrorist,’" Zakaria urged.

Zakaria worked tirelessly to build bridges in the community and legitimize the role of cultural resistance, careful not to discredit the right to armed struggle. He was dedicated to introducing young people to theatre and an alternative reality to that of death, destruction and trauma.

"I didn't want to become an armed resistance fighter," he said. "But this is what life gave me. I wanted to be an actor. I wanted to be Romeo. Now at The Freedom Theatre, others can have that chance."

As a team, we would stay up late arguing and dreaming about current and future productions. Zakaria seeded ideas, interrogated themes and dared us to dream bigger. His intricate understanding of the Palestinian struggle and determination to use theatre to confront internal corruption and social issues made his perspective crucial.

With his body marred by nine bullet wounds and his face covered in green speckles and eyesight severely damaged by a grenade, he often seemed vulnerable as he quietly smoked, contemplating the latest creative idea.

Yet Zakaria was indestructible. Upon news that the army was entering Jenin, he disappeared instantly, across rocks and brambles in flip-flops, protecting his life and ours. I once asked why his story had not been made into a film or play: "Because no audience would believe it," he said.

Death, raids and threats

In April 2011, Juliano was murdered outside the theatre by an unknown masked gunman.

Despite losing another friend, Zakaria put his grief aside to spend time meeting Palestinian officials and asking them to condemn the murder. He encouraged the mosque to announce Juliano as a martyr and put posters up around the camp. These small but mighty acts cemented the importance of cultural resistance and gave the theatre legitimacy to continue its work in the community.

In the coming months, there were raids and arrests of theatre staff by the ‘Israeli’ army and further death threats. Zakaria continued to be a protector of culture, and us, giving each person the confidence and wisdom to continue Juliano's legacy.

In May 2012, Zakaria was arrested by the Palestinian Authority, who forced him to drink toilet water, inflicting sleep deprivation, stress positions and solitary confinement. It was a humiliating experience at the hands of his own government, yet his approach was creative, telling friend and artist Micaela Miranda: "We could do a play about this."

Four months later, still held without charge, he declared a hunger and thirst strike: "This injustice not only robs me of my freedom but damages freedom for all. I am now fighting a new battle in Jericho prison with the only weapon I have left – my own life."

With just days to live and no one doubting Zakaria's determination, he was released.

Then in a twist of irony, he had to hand himself back to the Palestinian Authority over fears he would be assassinated by ‘Israel,’ who had revoked his amnesty in late 2011.

Zakaria was allowed a computer, internet and visitors, so he was able to participate when we created a play about the fighters in the 2002 siege of The Church of the Nativity.

A tour of the production in Britain was met with protests, and legal action, claiming we were promoting "terrorism."

In fact, it was Zakaria who had encouraged us to include a critique of the armed resistance.

He knew that the best way to succeed in liberation was through reflection, and theatre was the space to do that. Watching a video of the play, he was proud, whilst teasingly pointing out that it was clear some of the actors had never held a gun.

Arrest, escape and recapture

Once out in 2018, Zakaria embarked on a master's degree at Birzeit University. Then in February 2019, we woke to the news that he had been arrested by ‘Israel’ with the ‘Israeli’ spy agency, Shin Bet, claiming "he had shot at ‘Israeli’ buses."

Two and half years later, with no trial date set, from the depths of a high-security prison, Zakaria, alongside five others, dug a tunnel using a spoon and escaped.

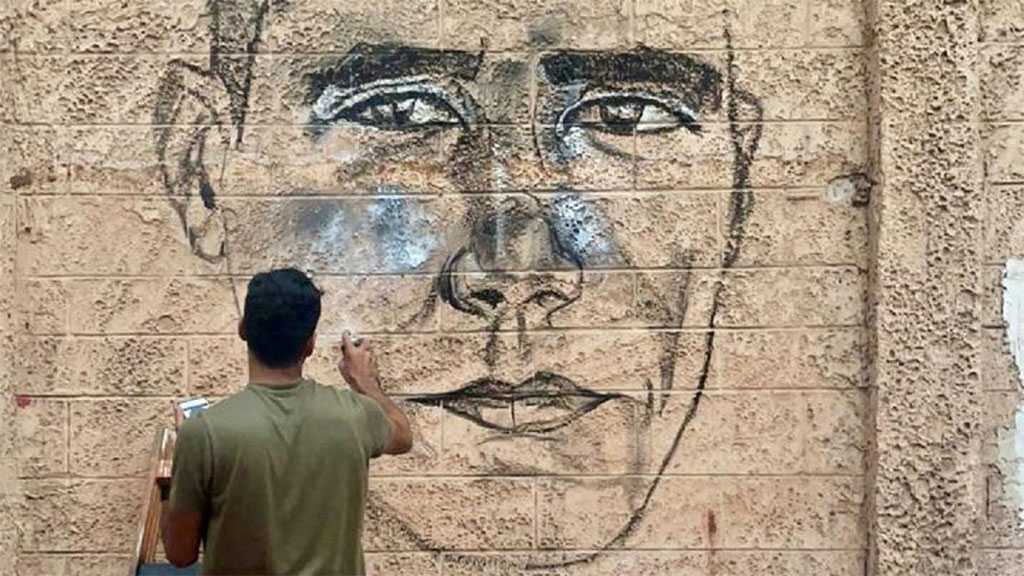

Inspiring a nation, workers went on strike in solidarity, sweets were handed out in celebration, banging spoons became a symbol of resistance, and artist Mohammad Sabaaneh created political graffiti around Palestine.

After five days, Zakaria was captured. There has still been no trial set for his original arrest, yet he has been given an additional five-year sentence for his escape.

And on 15 May, the anniversary of the Nakba - which Palestinians mark as the event when thousands were expelled from their homes during the ‘Israeli’ entity’s founding in 1948 - Zakaria's brother Daoud was killed by ‘Israeli’ gunfire.

Giving victory signs from the courtroom, completing his master's thesis from his cell and witnessing a flourishing young generation of Palestinian artists, Zakaria continues to teach me about the importance of reclaiming the narrative whatever the odds, and the power of spontaneity, creativity and imagination.

He is an example in arts that should be revered, a leader of acts of resistance too epic to be believed in any film, and a life that holds a revolutionary message more powerful than any writer could script.

Comments