‘There Is No Safe Space for Me to Be Myself’: The British Muslim Women Targeted For Their Beliefs

By Saman Javed – The Independent

“It’s one of the worst identities you could be,” says Aysha Yaqub on being a Muslim woman in the UK. At 27-years-old, Yaqub has been on the receiving end of countless death threats and verbal abuse because of her religion. According to statistics from the Home Office, Muslims were the target of 2,703 religious hate crimes in the year ending March 2021 – 45 per cent of all those recorded.

MEND, a charity that seeks to tackle Islamophobia in the UK, predicts the true extent of hate crime towards Muslims is likely much greater as many, like Yaqub, never end up filing a report with the police. “As one woman once told me, ‘if you want me to report the comments I receive for wearing a niqab, that’s all I would be doing all day’,” says Shockat Patel, a MEND board member.

This November marked Islamophobia Awareness Month [IAM]; an annual campaign co-founded by MEND which aims to highlight the discrimination Muslims face across different sectors of society. This year, groups have been calling on the government to adopt an official definition of Islamophobia as proposed by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on British Muslims [APPG]. In a 2018 report, the APPG wrote: “Islamophobia is rooted in racism and is a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness and perceived Muslimness.”

While the definition has been accepted by the Labour Party, Liberal Democrats and the London Mayor’s office, a government spokesperson told the BBC in 2019 that it needed “careful consideration”. Two years later, there is still no formal definition.

Although there are no known statistics around which demographic is most affected by Islamophobia, MEND’s work shows that those who appear visibly Muslim, such as women who wear the hijab or niqab, are likely to be targeted. In a parliamentary debate on 24 November, Labour politician Afzal Khan said defining Islamophobia is “the first step in rooting it out” and will “establish a mechanism for accountability”.

This sentiment has been backed by MEND, which said the absence of a definition has allowed Islamophobia against visibly Muslim women to “permeate all sections of society”. “Lots of women say they are fearful of going out, just because of the fact they are wearing a headscarf. For those that wear a niqab [the garment that leaves only eyes visible] they find it even more difficult because they know, almost certainly, that they are going to get verbal abuse,” Patel says.

Hamida Agarwal, who converted to Islam more than 15 years ago, says she had never experienced any form of racism until she began wearing a headscarf, despite being a brown woman. “I conformed, and I fitted in. I drank alcohol, I dressed the way everyone else dressed. But as soon as I put the hijab on everything changed,” she says. “The way people looked at me, the comments that were made, I just couldn’t believe it. It was really difficult to now live this life where everywhere you go, you’re now on the defensive and feel like you have to break a stereotype.”

One common assumption members of the public would make upon seeing Agarwal’s headscarf is that she couldn’t speak English. “I would be in the supermarket and the cashier would talk to my husband instead of me, thinking that I couldn’t respond to them,” she recalls.

Muslim women experience Islamophobic microagressions every day, whether it be at work, at university or even online. Rana Yusuf, a doctor who works in the NHS, described a workplace where microaggressions happen often. She says these are difficult to prove and hard to report.

Examples include overhearing colleagues describe Muslims as “a little bit backwards and weird” while discussing the news of Malala Yousafzai’s marriage, and being told by a nurse that she could not wish a Muslim colleague “Ramadan Mubarak” – a greeting Muslims use to wish each other a happy Ramadan – because she was not “speaking English”. “It was just one phrase in a totally English conversation,” Yusuf explains.

On a separate occasion, she recalled doing ward rounds with a senior consultant when the conversation turned to her personal life and he asked whether she would marry an English man instead of a Muslim man, as he said it was “important for your communities to integrate”. “It was really awkward because this is supposed to be the person that I should feel comfortable going to if a patient is not well, or if I feel out of my depth, but after having an interaction like that it makes me feel like I want to limit my interaction with him as much as possible,” she says.

When contacted by The Independent, the NHS said that Islamophobia and any form of discrimination is “unacceptable” and “will not be tolerated”. “It is absolutely deplorable for anyone in the NHS to feel unsafe on the grounds of their religious belief or practicing their faith and NHS organizations should take a zero-tolerance approach to all and any form of discrimination and take stringent action when reported,” a spokesperson said.

Khadija Khan, a former student at the University of Glasgow says a lack of understanding of what Islamophobia is and how it affects Muslims made it difficult for her to take part in discussions around the Middle East, Palestine and religious extremism that were integral to her studies. “Some of the things said in class by other students who were white and non-Muslim should 100 per cent have been challenged as Islamophobic, but it was really exhausting to have that onus on me because my tutor or lecturer was letting them be said,” she says.

Khan says she initially challenged some of these views but stopped over time after a tutor told her that “a successful student should be able to detach themselves from personal and emotional feelings they have towards a subject”. “It’s easy for someone to make Islamophobic comments when it doesn’t affect them, but when it’s your daily lived experience you’re obviously going to be affected,” Khan says.

A University of Glasgow spokesperson tells The Independent that they “encourage” anyone from the university to come forward if they have experienced “unacceptable behavior” such as racial discrimination. “Our Understanding Racism, Transforming University Cultures report published earlier this year recognizes that there can be a reluctance to report such harassment and we know there is more for us to do to further strengthen our processes,” the spokesperson explains. “Through the report’s action plan we are committed to being an anti-racist organization, to act decisively against racism and racial harassment on campus.”

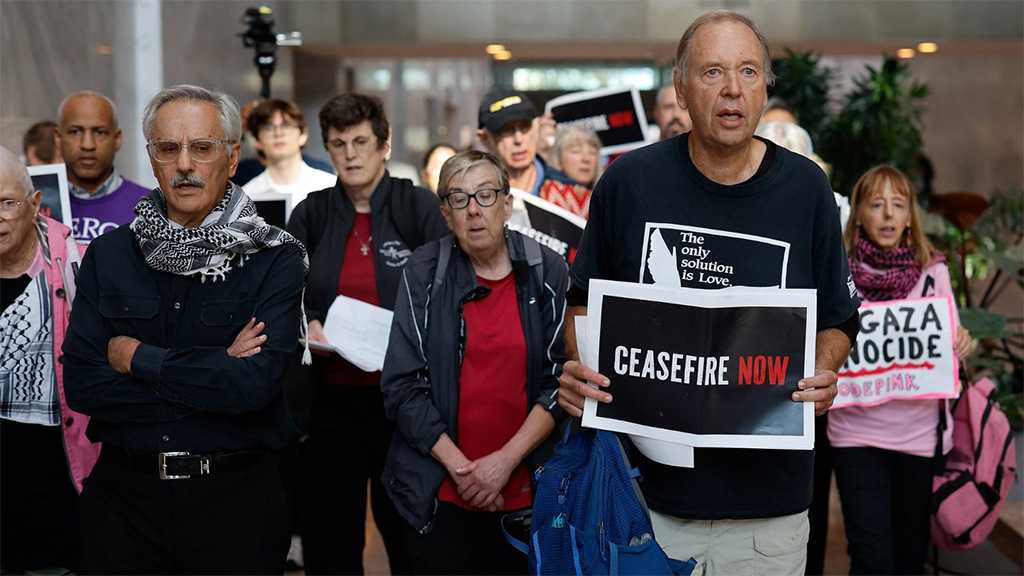

Patel says one of the reasons why Muslim women are targeted is down to “irresponsible reporting” by the media. On 30 November, the Muslim Council of Britain’s [MCB] Centre for Media Monitoring released a report which found that 60 per cent of online articles portray Muslims in a negative light. The report, titled British Media’s Coverage of Muslims and Islam [2018-2020], examined 48,000 online articles and 5,500 broadcast segments. The MCB said the use of stock images of visibly Muslim women to illustrate conflict and terrorism is one of the ways Muslims are often misrepresented by the media.

While many Muslim women experience verbal and physical abuse in public, they are also targets of hate online. Yaqub, an employee at the Muslim Association of Britain, often faces racism on Twitter which gets worse if her profile picture shows her hijab. “The minute they see a headscarf on your profile, that’s it, you’re a target. They don’t care where you’re from, for them being a Muslim is worse – it’s the worst identity you could have,” she says.

Yaqub says she can receive abuse for sharing her views on social issues such as universal credit or her opinions on the monarchy. “It’s crazy to me that my experience as a Muslim woman using social media is completely different to someone who doesn’t have those identity markers that make them a target for racial abuse and hate,” she says. When she has the time, she reports the abuse, but the response from Twitter is “hit and miss”. “If it’s very blatant racism, that kind of language is easier for Twitter to pick up. But sometimes the language is subtle,” she says.

While Yusuf did not openly receive hateful remarks about her hijab at work, she often felt nurses treated her less favorably than they did non-Muslim doctors. “As a doctor on-call, my work depended on nurses being receptive to me, but as a visibly Muslim woman coming on to new wards, I very much got a frosty reception.” she says. Her suspicions were confirmed when she stopped wearing a hijab one year later and felt a significant shift in the way she was treated. “The principal reason behind my decision is that I wanted to be invisible. I wanted to come in and do my job and go home, and not have people reacting to me,” she says. “I noticed a massive difference when I stopped wearing the hijab. I was very much the same person, with the same knowledge but I was just getting much better responses from nurses and colleagues.”

According to the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics, there are approximately 3.4 million Muslims in the UK, making up around five per cent of the total 67.2 million population. In 2018, a report by Ipsos MORI found that 57 per cent of the UK population feel they do not have a “good understanding” of Islam. This figure increased to 72 per cent among those who do not personally know someone who is Muslim. Researchers said this lack of understanding is likely to give rise to misconceptions, with 62 per cent of respondents stating that they believe Islam negatively impacts the quality of life of Muslims.

One common theme reported by Muslim women is how false perceptions of Islam often make them feel “othered” and “silenced”. Khan eventually stopped participating in seminar discussions in a bid to “blend into the background” but ultimately had a less rewarding university experience because of it. “It was difficult to be enthusiastic about going to university. Every day felt more exhausting than the day before,” she says.

For Yusuf, Islamophobia meant silencing her own beliefs, in order to feel accepted at work. “It’s not fair and I miss my hijab, but it was just getting too hard on a daily basis,” she says. Yaqub says the constant barrage of Islamophobic abuse she receives on Twitter has affected her ability to tweet freely, making her feel like she is being “driven out” of all aspects of public life. “I think 10 times about the language I’m using, about whether I’m going to get abuse for what I’m writing, and whether I should be commenting on common affairs,” she says. “This is what silencing looks like, when someone is driven away and made to feel like they can’t participate in a space – there is no safe space for me to be myself as a Muslim woman.”

Comments