How Did Syria Control the Pandemic So Well?

By Tim Anderson – American Herald Tribune

How is it that Syria, targeted by war and economic siege, has had such striking success in controlling the COVID19 pandemic? With epidemics raging on either side – across Europe and all around the Persian Gulf – how did the embattled Syrian Arab Republic emerge [by mid-June] with so little damage, and indeed with the lowest number of cases and deaths in the entire Middle East region?

This was not due to luck, nor to a laissez-faire Swedish style practice, as some pandemic denier friends of Syria have reported. On the contrary, the Syrian government: (1) took the virus threat seriously, communicating and maintaining trust with the Syrian people; (2) imposed strong quarantine and sanitary controls, but kept them under revision, flexible and targeted, so far as possible; and (3) imposed its quarantine and sanitary measures rapidly, well before the first infection was even detected.

That rapid response was critical. Like a forest fire, if a new and potentially dangerous virus is not controlled early, it will rage out of control for much longer. We saw that in the US and the UK (and Brazil, Ecuador and Chile), where leaders refused to take the threat seriously for many weeks, and were forced to act only when infections and deaths had reached into the thousands. In Syria the threat remained low, while in the US and Britain the crisis was deep, prolonged and facing resentment, aggravated by heavy handed and belated controls.

By contrast, the Syrian government acted rapidly to mobilize its health system, close borders and close schools, before they had detected any infections. Soon after the first case was found the government imposed a night-time curfew, to prevent large gatherings. Curfews had rarely been used, even during nine years of war. That rapid response helps explain why, by 18 June, there were less than 200 cases and only 7 deaths in Syria. This is despite the fact that the country was still occupied by three foreign armies and their proxy terror groups.

As part of its propaganda war, the US government attacked Damascus precisely for its protective measures, claiming ulterior motives. An article in the US state media (Gavlak 2020) claimed that the Syrian Government, “to consolidate its control … has practiced misinformation and intimidation over COVID19 from the start … it threatened hospitals and doctors that cited coronavirus cases. It deployed members of its secret police in hospitals.” US sources claimed (without much real evidence beyond media rumors) that Syria had more infections and the Syrian Government was covering them up.

Citing studies by a US foundation and a US-based cybersecurity firm, the article claimed the Damascus government had “planted spyware in citizens cell phones” and that its “repressive” practices included imposing a night-time curfew, restricting travel between provinces, shutting schools and universities and banning gatherings at mosques and other public events (Alkoutami and Fahim 2020; Gavlak 2020). Apart from the spyware claim, the other measures are uncontested. The Syrian government spelt out these measures in daily public reports, beginning in early March 2020.

Many western left-liberal pandemic deniers, including friends of Syria, repeated the same general criticisms, while remaining silent over Syria, or pretending that the government had barely acted at all. They attacked the WHO and the use of life-saving vaccines, while saying nothing about Syria’s collaboration with the WHO or its mass vaccination campaign. Yet Syria was clearly not part of any US-centered ‘conspiracy’ to lock up and medicate entire populations.

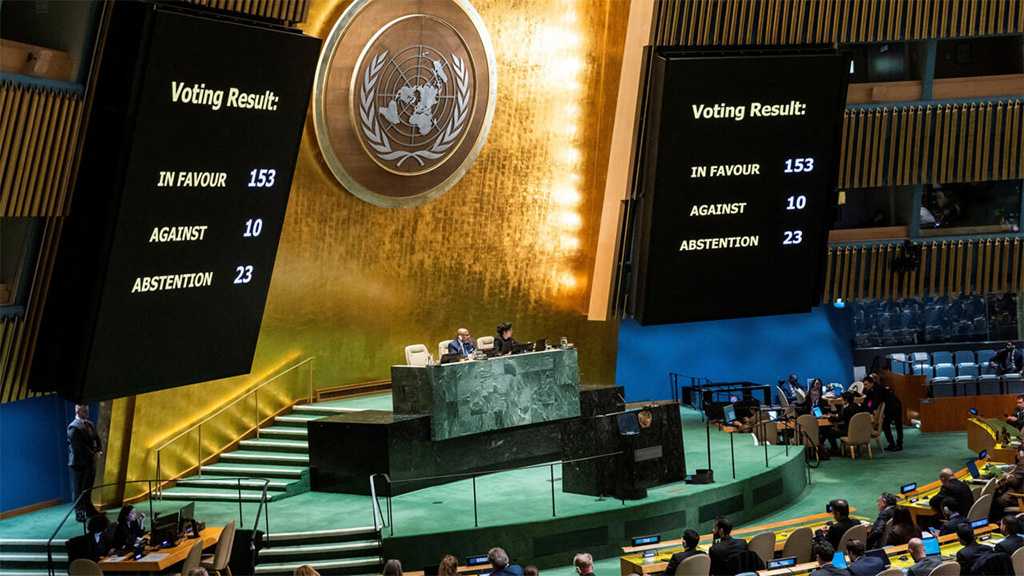

To get a better picture, let’s review Syrian policy and practice, from the beginning. All the Middle East governments were reporting serious COVID19 epidemics, and closing their borders. By 19 June 2020 Iran had reported 9,272 COVID19-related deaths, Turkey 4,882, Egypt 1,938, Saudi Arabia 1,139, Iraq 856, ‘Israel’/Palestine 312, Armenia 309, Kuwait 308, the UAE 298, Greece 188, Qatar 86, Bahrain 55, Tunisia 50, Lebanon 32, Jordan 9 and Syria just 7 (Worldometer 2020). So how did Syria achieve much better outcomes than its neighbors?

On 3 March Syria had no COVID19 cases, but the Health Ministry formed an emergency committee with branches in each province. They developed a “national work plan to confront the virus” along with the development of diagnosis kits, quarantine facilities and training of medical staff. On 13 March the country had still not detected any cases, but the Health Ministry was promoting awareness and asking that citizens “should go to hospital when they come up with the symptoms of the virus”.

Schools and universities were also suspended on 13 March, and work hours were cut. On 15 March the cabinet approved a plan which focused on making ready sanitary products and medical equipment for diagnosis and quarantine. Some additional decisions on how to deal with the epidemic were made between 17 and 22 March, while tests carried out on 31 people at Damascus Airport proved negative.

However, on 22 March the first case (a person from abroad) was detected. On that same day all public transport and private transport between the provinces was suspended and crossing points to Lebanon were stopped for all except cargo trucks. Cabinet adopted the plan of the Health Ministry to expand quarantine and isolation centers, with 19 emergency teams and additional diagnosis labs (in Damascus, Lattakia and Aleppo), “in cooperation with the World Health Organization”.

Night-time curfews from 6 am to 6 pm were imposed in Damascus on 24 March and in Aleppo on 25 March, and a nation-wide curfew was put in place on 31 March. A total curfew was imposed on the Tartous sea waterfront, on 2 April, until further notice, while more total ‘lockdowns’ were imposed on the shrine town of Al Sayeda Zainab and the tourist spot of Tal Mnin, Damascus areas which were considered ‘hotspots’ of infection. On 3 April the Friday and Saturday curfews were extended from 12 midday to 6 am the next day.

A Damascus doctor told me on 24 April that shops which had been closed were being opened at special times for example: clothes shops on Monday and Wednesday. Syria's Health Department coordinated with the WHO, which was providing some test kits. The WHO representative also “appears on our TV and radio”.

Syria’s President Bashar al Assad, himself a medical doctor, was seen wearing a face mask in his 20 April meeting with Iran’s Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, who was also wearing gloves. This was likely a precaution against infections from Iran, which at that time had the highest level of infections in the region. It may also have been to show an example of precautionary behavior. Syria did not adopt any requirement for wearing face masks. However, it is clear that Syria’s low levels of infection did not prevent President Assad from taking the virus seriously. In early May he told the Government Committee which oversees the pandemic response that the low level of infections did not mean Syria had escaped the “circle of danger … these figures could suddenly spike in a few days or few weeks and we would see in front of us real catastrophe that exceeds our health and logistical abilities”.

A member of the Ba’ath Party told me the curfew period had been “devastating”, as there was “no income no food nothing” and everyone had their own struggles. Yet when Ramadan arrived on 23 April the curfew was set back to start at 7.30 pm. That adjustment showed some flexibility and adaptation, as did the subsequent lifting of closures on Al Sayeda Zainab and Tal Mnin.

Syrian nationals kept returning to the country, across land and air borders, including by use of Syria’s national airline; even though this introduced new cases, particularly from Kuwait. However, they were all subject to screening, not too different from the procedures in other countries (a 14-day special quarantine period), except that they were housed and fed in fairly basic state-run facilities. Several thousand people were subject to this sort of preventive quarantine.

Eventually, on 26 May after 2 months of strong control measures and with a very low level of infections, the curfew was lifted completely. Nevertheless, the Health Ministry warned that there was “still a possibility of a full curfew in the future depending on developments related to the pandemic”. The quarantine measures had been imposed rapidly but were also relaxed rapidly, as a result of the country’s relative success. Schools, which had gone online since March, began a cautious reopening. A Damascus headmistress told me that year 9 and 12 students were returning for their exams on 21 June.

The overall Syrian approach was similar to that of Cuba, in that it was led by the Health Ministry, there was daily information from health authorities, strong quarantine measures were imposed, even before infections were detected, and severe lockdowns were imposed on specific ‘hot spots’ which had outbreaks of infection.

Similarly, Cuba began its quarantine measures several days before any detected cases, but aware of what had happened in other countries. The theme of ‘stay at home’ (quedese en casa) was put out in the Cuban media as early as 6 March, several days before the first detected case. Importantly, in both countries, and despite the measured restriction of liberties, the public maintained a strong degree of trust in health authorities. In Syria, this relationship and ‘commitment’, according to a former Syrian soldier, remains the key to Syria’s advances.

The quarantine measures in Syria were more severe than those of many other countries, such as my own country Australia. We had no curfew and some states did not close schools. Yet we had often arbitrary and changeable rules. An Australian minister said in June that his government would probably not allow tourism nor allow residents to leave the country “any time soon”. A mobile phone application to allow Australians to detect others who had been infected was at first pressed as a necessity but quickly became “irrelevant”. Much the same thing happened in Britain. Meantime, Syria has made clear initiatives for reopening, including reopening its borders in early July.

Accepting quarantine measures in principle (as distinct from criticisms likely to be made about restrictive practice, in particular contexts) also implies a measure of responsibility. That was lacking in many western cultures, where little regard was often shown for the impact on old, frail and disadvantaged people, and this particular virus hit those groups the hardest.

That disregard was shocking to Lebanese Resistance leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, who characterized the laissez-faire western approach in this way:

“‘Let these old people die, no problem, let's leave them alone without care or support, so that the youth, who are the country's future, workforce and economy, may survive’. This is a descent in humanity … on the contrary, when humans get older, our human and ethical responsibility towards them becomes much bigger, even when it comes to your choice of words with them. So how could we abandon the elderly? Why?”

The pandemic deniers who were friends of Syria, having also bought into the western anti-vaccine movement, remained silent when in mid-June Damascus resumed its long-standing campaign of mass child vaccination. With vaccines Syria had eliminated polio in 1997, tetanus in 1997 and had made key advances against measles. In the resumed campaign, eleven vaccines are being given to all children under five, especially the 240,000 children who missed out on vaccinations due to the war. Hundreds of centers and mobile teams were set up, including in those areas still controlled by armed gangs. More than 8,000 health workers were mobilized. Such campaigns are an essential part of all decent public health systems.

Latin American writer Pasqualina Curcio pointed out – as had I in a previous article ‘How the Pandemic Defrocked Hegemonic Neoliberalism’ – that the pandemic had highlighted the failures of neoliberal systems. These were systems which preached ‘liberty’ and opposition to ‘paternalistic’ public health systems, so as to facilitate private corporate control. Curcio (2020) also observed that the 3.7 billion people worldwide living in poverty were far worse affected by both the disease and the crash in their incomes and livelihoods. Subsequent studies have showed both the health and economic impact of the crisis falling most heavily on disadvantaged minorities. Black Americans were “dying of Covid-19 at three times the rate of white people”, and much the same burden fell on Black and Asian people in Britain.

So how did Syria produce the best results in its region? Even when facing an intensified genocidal siege from the US and the EU, the Syrian government was able to effectively defend public health. Damascus did not sit on its hands, like Boris Johnson, waiting for ‘herd immunity’ to sweep through the country. Nor did it, like Donald Trump, proclaim that the warmer weather would blow the virus away. The Syrian government acted quickly and decisively, to protect the Syrian people.

Comments