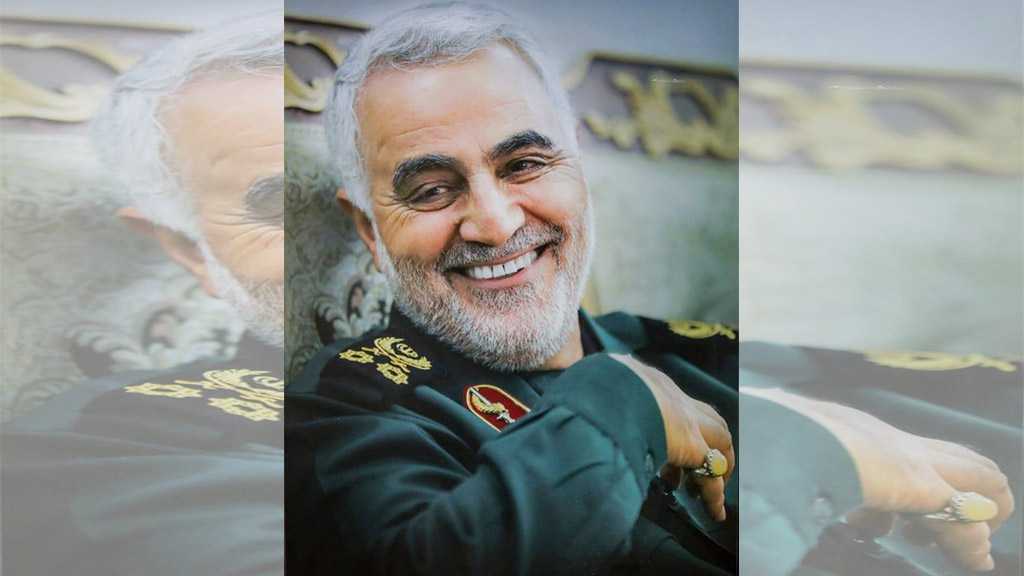

I Am Qassem Soleimani

By Khalil Kawtharani - Al-Akhbar Newspaper

Translated by Staff

“I am Qassem Soleimani, the commander of Sahib Al-Zaman’s seventh legion in Kerman Province. I was born in 1958 in the village of Qanat Malak on the outskirts of Kerman. I am a holder of a Baccalaureate degree. I am married with two children, a boy and a girl. Before the [Islamic] revolution, I was a contractor for the Kerman Water Organization.

And after the victory of the Islamic Revolution, I joined the Revolutionary Guard Corp’s on May 1, 1980. With the outbreak of war and the Iraqi regime's attack on the country's airports, I was tasked with guarding planes at the Kerman Airport for a while.

Two or three months after the outbreak of the war, we set out to the frontlines of Susangerd. We were among the first forces sent from Kerman, which included approximately 300 soldiers. I was a platoon leader at the time.

Soon after arriving on the front, I believed that the enemy was capable of doing anything. But during our first attack, we managed to force them to retreat from the side of the Susangerd road to Al-Hamidiya, and they incurred heavy losses.

This incident removed any false perception that I had about the enemy.”

(General Qassem Soleimani for "Nida Al-Thawra" magazine in 1990)

Thirty years later: Al-Bukamal is here

You should have seen him in Syria’s Al-Bukamal. The battle was at its peak. It was close-quarters combat, and he was only a few meters away. Martyrs were falling along the frontline on the outskirts of the city. At one instance, a Hezbollah fighter looked over at the enemy and then back at the Hajj who was indifferent to his personal safety. Al-Bukamal was the last major battle he had planned, led and as usual achieved victory.

Stepping into the light

Since the start of the war against Daesh, Qassem Soleimani was no longer the “Shadow Commander” – a label US newspapers gave him in 2009 shortly after the enemy sidestepped him in the assassination of Imad Mughniyeh in Damascus.

According to the leadership in Tehran, the top Iranian general stepped into the light with his public appearances on the battlefield. It marked a turning point in Iran’s influence and role outside its borders. Pictures of “Hajj Qassem" spread quickly among fighters on different fronts and throughout operation and meeting rooms.

As fighting in Iraq intensified, he began frequenting the Baghdad airport (his final stop on Thursday) with a logistical and armament supply line accompanying him. Soon, he gathered his allies in the Iraqi resistance that fought the American occupation. He then laid out a two-pronged approach. He set up plans to contain the expansion of Daesh and launched counterattacks. Meanwhile, he prepared training and organization programs for the fighting factions being assembled in response to the fatwa of the Marja’ as well as the formations that needed to accommodate thousands of new volunteers. Then the first of the large-scale battles was dubbed the Jurf al-Sakhar (rocky bank) operation.

Let American soldiers wear diapers

That was a war to defend Iraq and to protect Iran's borders and security at the same time. But it was not the first battle he fought to achieve both objectives.

Soleimani, the first contributor to founding and supporting the Iraqi resistance formations, worked according to an Iranian strategy. The strategy was founded on the belief that the US invasion of Baghdad was a prelude to targeting Iran. It was designed to ignite a war of attrition that would disrupt American calculations who were focused on Afghanistan and Iraq while also threatening Syria.

Soleimani had what he wanted. And at that point, the name of the commander of the Revolutionary Guard’s Quds Force began to echo.

On that day, a foreign policy strategy said to have been created by Imam Khomeini returned: One hand striking the enemy and another negotiating with it at the same time.

This course was solidified with the help of Javad Zarif’s smile and Qassem Soleimani’s frown.

Those working with Major General Soleimani remember many stories during Iraq’s resistance. They testify to his military and security brilliance that caused frustration among American officers and diplomats more than once. He eluded them in the spheres of security, military and even politics. One person who knew him credits “Persian savviness” for his attributes.

Donald Trump said Friday, “General Qassem Soleimani has killed or badly wounded thousands of Americans over an extended period of time.”

The general did not deny this accusation nor did he deny the fear that his bombs planted among American soldiers. On one occasion, he mocked the American soldiers' cowardice saying that US forces needed supplies of "adult diapers".

“The noble knight”

To his enemies in the West, he was the second most powerful man in the Islamic Republic. But in Tehran, that was neither his influence nor his rank. Nevertheless, he has been a legendary hero for over a decade.

To Iranian nationalists, he was an equal to the heroes found in legends of ancient Persian empires.

But he didn’t see himself that way and neither did his Islamic brothers in the Revolutionary Guards – those in Iran and the broader region.

He saw himself as "a soldier of the wilaya on the path to al-Quds (Jerusalem)", according to the literature of the Iranian revolution. His brothers in arms saw him as the bearer of the banner of this revolution, who was protecting the interests of the country on the one hand and keeping the flame of the revolution with its internationalist version ablaze.

The Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, called him the "living martyr". Meanwhile, the Iranians raised pictures of this man who came from a poor family – in a rare phenomenon that was reserved for Khomeini, Khamenei and the martyrs of the revolution such as Mutahari, Bahshti, Shamran and others.

To the enemy, he was the “man who did the dirty work”, “the butcher” and “terrifying”. He was all these when it came to examining the burden his actions exerted on “Israel”, the United States and its allies in the Gulf.

But one of the general’s companions called him the “noble knight”. He also spoke of the commander’s “fatherhood” role as well as his kindness and humility towards everyone. He sought merciful treatment even for the enemies he was able to annihilate.

He was a diplomatic negotiator, modest, perceptive, a gentleman, well-mannered and close to the heart. He never burnt bridges with anyone. He was energetic, took the initiative and "spiritual", according to his companion who also noted that these characteristics would not be obvious to anyone who watched his military action remotely.

The "prestige" of the axis ... and its pole

So, what did it mean to serve as the leader of the Quds Force that developed after the Gulf War from the womb of the Revolutionary Guards and to organize the external activities of the Guards during “peacetime”? It meant being responsible for external operations everywhere beyond Iran’s borders – at the very least in the region or West Asia as the Iranians call it.

This region is crowded with enemies that must be dealt with, including the US, Britain and Western forces in general, their Arab allies, “Israel”, Kurdish separatists and finally the Takfiri organizations.

At the same time, it is filled with allies and friends: Syria and the resistance factions in Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine and Yemen.

The task of Sardar Soleimani (Farsi for commander Soleimani) or Hajji Abu Duaa as the Iraqis called him was to pass on combat tactics the Revolutionary Guards learned from the eight-year war with Iraq and inaugurate its military industry based on this experience. These tactics included observing the enemy's armed superiority and confronting it with unconventional or asymmetric fighting. Its main pillar is the use of missiles versus air superiority.

Since taking up his post in the late 1990s, Soleimani was tasked with transferring expertise and armaments as well as constructing solid combat infrastructure for the allies. In a few years, the term "axis of resistance" would begin to feature prominently. In this axis, Soleimani was the architect and later its core, prompting some to call it the “Qassem Soleimani axis”.

The July war was an essential juncture to foment the experience. Soleimani’s decision-making role when it came to regional files (especially those related to resistance movements against “Israel”) Hezbollah in Lebanon, its Secretary General Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, and its military commander at the time martyr Imad Mughniyah became more independent by order of the Supreme Leader Khamenei.

In Gaza and Lebanon, and later in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen, the allies started to see Soleimani as a support for their movements. His fingerprints were behind every achievement and victory. His role was not limited to military aspects. He was very focused on the media and politics in a bid to ensure that allied movements were equipped with soft power and not just with weapons.

Perhaps the most important thing that helped him to diversify his experiences, and even to be chosen for this post, was his role as commander of the Revolutionary Guards in Kerman Province. The province is an area close to the Afghan border. There he worked in combating drug trafficking. That responsibility allowed him to experiment with security work and contribute to protecting the border where he achieved remarkable successes against the opium smuggling gangs.

Soleimani grew in prominence as the axis of resistance expanded. He became the first political and military player in the region alongside other branches in Tehran, which met in the Supreme National Security Council and were locked in heated debates. Opinions varied, and the final word may not have been Soleimani’s as some think.

A leader in the axis of resistance, who is familiar with its decision-making mechanism among different parties, elaborates and explains the significance of Soleimani's loss.

“The Guards is an institution”, he says. “The greatest loss from the assassination of the general is its effect on the ‘prestige of the axis’ that he helped to establish over the years.”

What about the things he didn’t get to accomplish?

One of those closest to him recently told Al-Akhbar, "Al-Quds was his practical program, his dream and his personal obsession that he was passionate about in private meetings!”

Comments