History Won’t Look Kindly On Britain over Arms Sales Feeding War in Yemen

Anna Stavrianakis

The war in Yemen has killed upwards of 57,000 people since March 2015, left 8.4 million people surviving on food aid and created a cholera epidemic. The British government claims to have been at the forefront of international humanitarian assistance, giving more than £570m to Yemen in bilateral aid since the war began.

Yet the financial value of aid is a drop in the ocean compared with the value of weapons sold to the Saudi-led coalition – licenses worth at least £4.7bn of arms exports to Saudi Arabia and £860m to its coalition partners since the start of the war. Relatively speaking, aid has been little more than a sticking plaster on the death, injury, destruction, displacement, famine and disease inflicted on Yemen by an entirely manmade disaster.

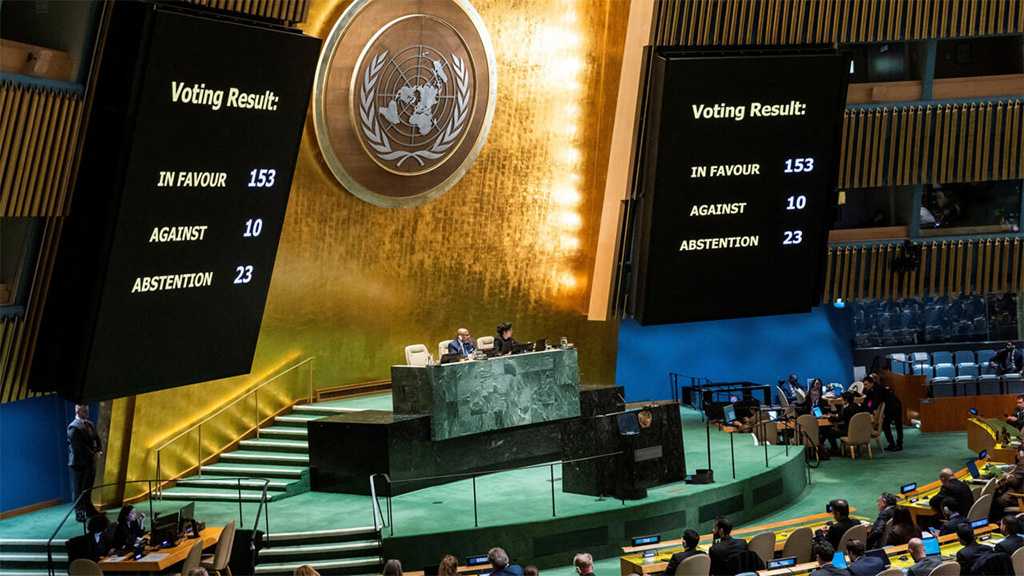

Britain and the US have been the key supporters of the Saudi-led coalition, providing arms, intelligence, logistics, military training and diplomatic cover. This has provoked criticism: in the US, a Democrat congressional resolution invoked the 1973 War Powers Act to end US involvement in the war in Yemen, but was blocked by a Republican procedural rule change to a resolution about … wolves. More recently, an attempt to push through a UN resolution calling for a ceasefire was stalled by the US and other countries, reportedly after a lobbying campaign by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates [UAE].

In the UK, parliament’s committees on arms export controls [CAEC] fell into disarray in 2016, unable to agree on whether or not to recommend a suspension of arms exports to Saudi Arabia pending an international investigation into alleged war crimes.

Britain’s own rules state that it cannot sell weapons to countries where there is a clear risk they might be used in serious violations of international humanitarian law.

The UK government claims to have one of the most rigorous arms control regimes in the world, yet evidence of attacks on medical facilities and schoolchildren in Yemen is clear.

War is the primary cause of death, injury, famine and disease in Yemen; and the coalition is causing twice as many civilian casualties as all other forces fighting in Yemen.

There are some responsible for holding the government to account for arms sales…

First, by batting away extensive evidence of violations of international humanitarian law, claiming it can’t be sure they have happened – despite a risk-based framework that is explicitly preventive in orientation.

Second, by working with the Saudis to claim that, if attacks on civilians have happened, they must have been a mistake.

Third, that any past misuse of weapons doesn’t necessarily mean future misuse. According to the British government, while there may be a risk of weapons being misused in Yemen, that risk is not clear.

The upshot is an exponential rise in arms sales since the war started, to the point where Saudi now accounts for almost half of UK arms exports.

The government has been forced to expend greater energy in justifying its position and devote more resources to the aid response – even if it will not rein in arms sales, the key aspect of UK complicity, as admitted by the former defense attaché to Riyadh last month.

There is another aspect of British arms export policy that is contributing to the war: the approval of brokering licenses for weapons that have ended up with Saudi and UAE proxies in Yemen, as well as Libya and Syria.

Brokering is facilitating [rather than directly supplying] the transfer of weapons from outside Britain to a third country. Since 2012, in the counter-revolutionary backlash against the Arab spring across the Middle East and north Africa, the Saudis and the UAE, alongside Jordan and Turkey, have purchased weapons worth €1.2bn [£1.08bn] from eastern and central European countries – notably the former states of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, and Serbia, Croatia and Bulgaria – for onward re-transfer to allied proxy forces in Yemen, Syria and Libya.

In June, the British government was exposed to embarrassment when it emerged that it failed to notify the Bosnian government of its intention, based on a decision made in March 2016, to refuse a brokering license for almost 30m Bosnian-made bullets to Saudi. By the time the license was refused, on the basis of an unacceptable risk that the bullets would be diverted, they had already been shipped.

This was an unusual case. The UK government admitted that its Saudi client was not reliable, that the specified end user named on the paperwork was not the intended final recipient, and that the Saudi military was sending weapons on to clients in Yemen.

It seems the UK government can sometimes decide there is a clear risk – but even then prove incompetent at addressing it.

As calls grow for an embargo on Saudi Arabia and a peace process in Yemen, this litany of British deceit, mistakes, bureaucratic malfeasance, and political maneuvering – all to support a friendly yet wantonly reckless regime – will not be judged kindly by history.

Source: The Guardian, Edited by website team

Comments