A Day in Hizbullah’s Martyr Cemetery

By: Mohamed Nazzal

al-Akhbar, 14-11-2012

Over a decade ago, as a young man, Rabie attended his first martyr funeral. The funeral procession for Rabie Wehbi - no relation to the other Rabie - twisted through the streets of Dahiyeh and ended at Rawdat al-Shahidain cemetery. Rabie helped carry the shrouded body, and threw soil into the grave.

After everyone left, he stayed behind. Emotions overtook him and compelled him to stand by the grave until sunset. Rabie wanted to become a resistance fighter like him. He resolved that he would.

After everyone left, he stayed behind. Emotions overtook him and compelled him to stand by the grave until sunset. Rabie wanted to become a resistance fighter like him. He resolved that he would.

There is nothing about Hadi's grave that distinguishes it from the others. Nevertheless, since that day, the cemetery was transformed.

Rabie joined the ranks of the Resistance, and the image of Rabie Wehbi the martyr has always remained with him. Barely a week passes without him visiting the cemetery, and he always goes to Wehbi's grave first.

0At the time of that funeral the Hizbullah martyrs' cemetery was relatively small. It was simple and there was no roofing. Nothing but soil separated the graves.

By 1998, Rabie had attended the burials of several other fighters there. That year, he was in the crowd when Hizbullah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah led funeral prayers at the Raya playing field for dozens of martyrs whose remains had been returned by "Israel", including Hadi Nasrallah, his son. Rabie repeated after him, "God, accept this sacrifice from us," and marched in the funeral procession.

There is nothing about Hadi's grave that distinguishes it from the others. Nevertheless, since that day, the cemetery was transformed. It became a destination for delegations of admirers and supporters, impressed by a party that treats the grave of its leader's son no differently than others. Hadi's grave is perhaps even less festooned than the others; for security reasons, his parents are unable to visit.

Yet there is a constant stream of visitors to Hadi's grave, said Rabie. People who never knew him in life visit him in death to say their prayers and touch his tombstone.

In 1998, while on a Hizbullah military training course, Rabie met someone who was as devoted as he was to the martyrs, Fadi. The two became close friends. They used to meet after training at Rawdat al-Shahidain. Sometimes they would spend hours there, reciting the Quran or contemplating the martyrs' faces.

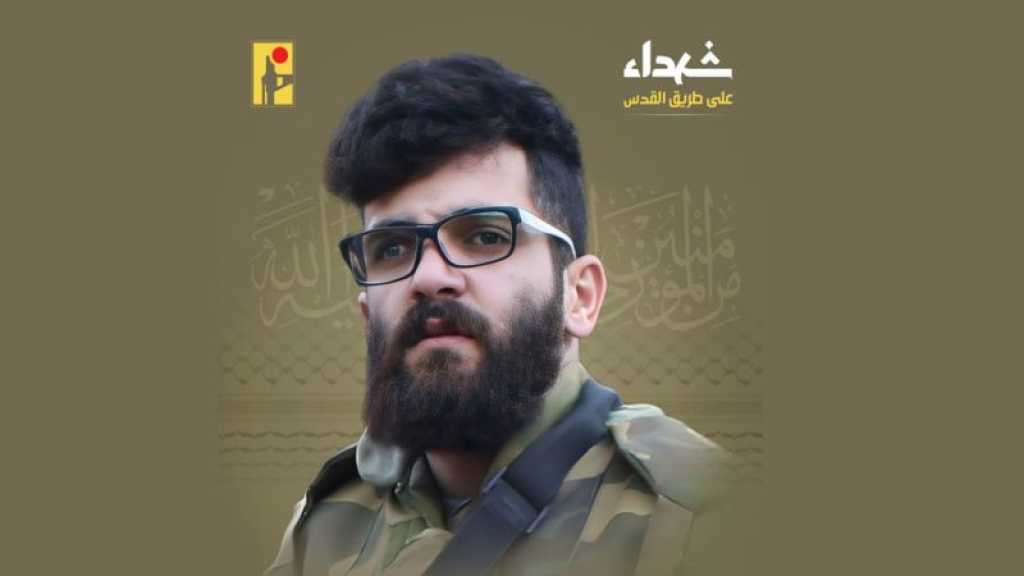

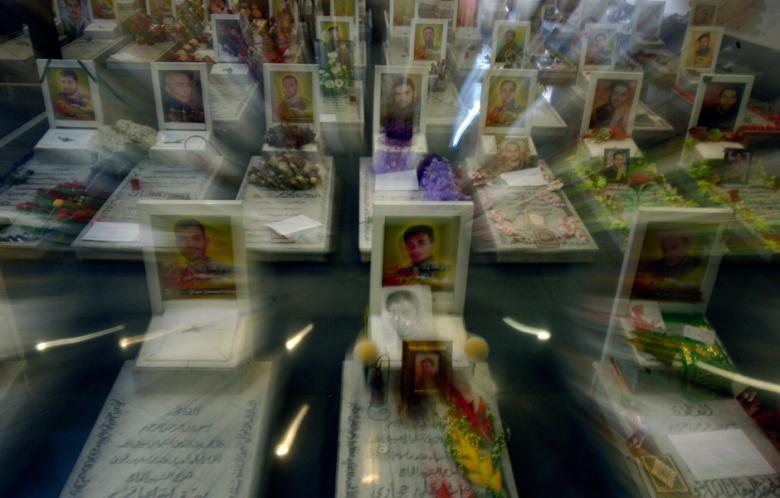

There are 107 graves in the Rawdat al-Shahidain cemetery. On each tombstone, there is a photograph of the martyr - with only a few exceptions - along with the place of their birth and frequently the operation in which they served. Others read, "Martyred in the course of performing his jihadi duty" - an all-encompassing phrase used by Hizbullah to cover anything from death in a car accident to a heart attack, as long as it occurs while on duty.

It was some time before Rabie found himself at another funeral. This was for Ali Zahri (known as Hajj Abdul-Rasoul), whom he had met some months before in the South. Ali was renowned among the Resistance fighters. He was featured in a famous video clip of a unit that attacked an "Israeli" army position in Sajd, taking the oath while standing by a flag he had planted on an embankment.

After Ali, the time came to bid another farewell, this time to his friend Fadi Ghazal (Qasem). His former training partner was killed two months before liberation in 2000, but his body was only recovered afterwards, brought to Beirut and interred in the Rawda.

Near Fadi's grave is a group of tombstones bearing the inscription "Martyr of Unknown Identity." All that is known of them is that they were martyred on 7 June 1990. Theirs were among the remains recovered from "Israeli" authorities in various exchanges, but by the time of their arrival, their condition had so deteriorated that they could not be identified.

Last Thursday, just ahead of Hizbullah's annual Martyrs Day commemoration on 11 November 2012, a mother of two martyrs was deep in silent conversation with her sons, immersed in her private world. Hassan and Ali Muslimani both died on 9 August 2006. Their mother will never forget it. "It was one of the proud days of the June war," she said.

The mother is not talkative. She is busy tending to the graves and arranging flowers. She expressed a wish: "I want to be buried here after I die, in the grave containing my son."

On each tombstone, there is a photograph of the martyr along with the place of their birth and frequently the operation in which they served.

Other mothers have had the same wish fulfilled. Rabie Wehbi's mother Samira Salha asked to be buried in his grave, and the headstone now bears both their names. Sahjanan Alawiyeh joined her son 13 years after his martyrdom, while Daloul al-Habhab was reunited with her beloved Mohammad seven years after they parted.

Rabie witnessed all of this. He has been watching the mothers visiting for years. He recognizes their faces and knows their different graveside rituals. He has seen a succession of martyrs' processions coming to the cemetery, and has become something of an authority on the literature of martyrdom.

Rabie has much to say about the term "martyr." He feels it is used excessively and inappropriately these days. He cannot understand how someone like Ali Zahra, who gave his all in the South, can be likened to people "who were killed God knows how and why."

While stressing his respect for all the dead, he said, "I will personally continue to allow myself only to call those who are killed in the cause - the cause that lies to the South - as martyrs."

For Rabie, martyrs are people like Hizbullah military commander Imad Mughniyeh, whose funeral he also attended. One visitor to Mughniyeh's grave said he goes there daily to touch the gravestone. This section has other regular visitors who are not related to the martyrs. They say they come to escape from the hectic world of the living and find peace among the dead.

These days, Rabie goes to the cemetery unaccompanied. He is pleased at the growing number of visitors to the martyrs' graves. Rabie venerates those who have been killed. He is privy to secrets and he is keeping them. Maybe he will be able to reveal them one day. Or maybe his wish will be fulfilled and he will rejoin the companions who left him, those he calls "the guides of the procession of existence."